The High Altar of Gorton Monastery (Church of St Francis, Manchester)

Design and Original Construction (1860s–1885)

The former Church of St Francis (Gorton Monastery) is a High Victorian Gothic masterpiece designed by Edward Welby Pugin in the 1860s. The church’s crowning feature is its high altar and towering reredos at the north end of the nave, which became the focal point of the interior. Notably, the high altar was not completed until over a decade after the church’s 1872 opening. In 1883–85 a new sanctuary and high altar were constructed, designed by Pugin’s half-brother Peter Paul Pugin (of the firm Pugin & Pugin). The high altar and its reredos were consecrated in 1885 and were acclaimed as “one of the largest in England” at that time. Rising to over 40 feet (12 m) in height, the reredos forms an elaborate Gothic screen behind the altar.

Materials and craftsmanship

The altar ensemble was richly constructed with a polychrome array of materials. The main altar mensa (table slab) is carved from pure white Italian marble, supported by eight polished “Californian marble” columns. The broad reredos behind the altar is structured in tiers: its base is Irish marble, above which runs a band of carved alabaster and a moulded string-course of black marble.

The reredos is divided into bays with panels of inlaid marble and open Gothic tracery, bristling with crocketed gables and finials in the 13th-century Gothic style. Gilded inscriptions (such as “Sanctus”) and carved Eucharistic symbols adorn the lower panels. Sculpted figures of saints and angels populate the structure: for example, canopied niches contain statues of St. Anthony, St. Francis, St. Clare, St. Dominic, St. Bonaventure, St. Elizabeth of Hungary, and other Franciscan patrons, each statue sheltered under delicate traceried canopy work.

A central arched canopy (tabernacle throne) rises above the altar, supported by marble shafts and flanked by airy open-work flying buttresses – a miniature echo of a medieval cathedral façade. The tabernacle itself was fashioned from alabaster with a brass door, surmounted by a pelican symbol and an alabaster cross. Every element was executed with fine detail: the entire altar and reredos were hand-carved on site. Franciscan Brother, Patrick Dalton, (the friary’s clerk of works) supervised the work, and the decorative carving was carried out by the renowned ecclesiastical sculptor Mr. Boulton of Cheltenham.

The sumptuous Gothic design, with its combination of stone, marble, alabaster, and gilded metal, exemplified the Pugin family’s high church design ideals. It created a dramatic visual focus for worship; a true “high altar” in both scale and intent.

Layout and stylistic influences

Unusually, Gorton’s church is aligned north–south due to the urban site, placing the high altar at the north end rather than true east. This allowed Edward Pugin’s design to incorporate a grand entrance at the south end and a clear, uninterrupted view straight down the nave to the high altar as one entered – a liturgical trend of the 1860s that Pugin favored. High in the chancel roof, large dormer windows were positioned to flood sunlight onto the high altar, theatrically illuminating the reredos and its statues. This play of light was intentional, dramatizing the ornate altar as the spiritual centerpiece of the space.

The overall style of the altar is Gothic Revival in the late-Decorated mode – richly textured with tracery, niches, pinnacles and polychrome elements – reflecting the influence of medieval English and continental Gothic altarpieces. Contemporary descriptions from 1885 praise the high altar’s lavish detail, calling it “very elaborate in decoration”.

With its lofty spired canopy and multitude of sculpted saints and angels, the altar reredos at Gorton was a showpiece of Catholic revival art, meant to inspire awe. In essence, Peter Paul Pugin’s high altar translated the Pugin family’s Gothic ideals into one of Victorian England’s most impressive church furnishings.

Decline, Losses and Restoration Challenges (1989–2000s)

By the late 20th century, the fate of this magnificent altar took a tragic turn. The Church of St Francis was closed in 1989 amid parish consolidation and was sold to developers. The building was subsequently stripped of its interior fittings – the oak doors, pews, organ and many statues were removed for salvage. Left unmaintained, the abandoned “Gorton Monastery” suffered severe deterioration. Water ingress and vandalism caused extensive damage to the delicate painted plaster and stonework of the altars and walls. Worse, thieves and looters targeted the ornamentation: “vandals moved in, [and] thieves stole pieces of the altar, designed by Paul Pugin,” reported The Guardian.

The once-grand high altar was effectively ransacked, with many of its statuettes, carved details, and marble elements smashed or pilfered in the 1990s. By the time preservationists intervened, only remnants of the structure survived in situ. One restoration account noted that “all that remains [of the high altar] are the stone steps and the brick base,” with much of the reredos collapsed or missing beyond the central section.

These losses underscored the monumental challenge facing any restoration: the high altar had to be rescued from the edge of ruin. In 1996 a local volunteer team formed the Monastery of St Francis & Gorton Trust to save the building. Thanks to emergency stabilization and fundraising (aided by the World Monuments Fund, which listed Gorton Monastery among the world’s 100 most endangered sites), a major heritage-led restoration project began in the early 2000s. The initial phase focused on making the derelict structure safe and usable. By 2007, the Grade II* listed monastery was reopened as a public venue after a £6 million renovation. However, due to limited funds, many interior furnishings were not fully restored at that stage – and this included the high altar and reredos. Conservation architects saved and stabilized the remaining portions of the altar structures (preventing further collapse), but a full aesthetic restoration was deferred.

In practice, the approach was one of “honest repair” – the altar and reredos were left with visible scars of the neglect and lovingly conserved in their fragile state, rather than being completely rebuilt anew. For example, early decorative paint flakes on the wall behind were conserved in situ by carefully re-adhering plaster fragments, and damaged stone elements were patched to be structurally sound but not overly refurbished. By 2007, visitors could once again admire the high altar’s form in the Monastery’s apse, but it stood as a ruined grandeur, awaiting more thorough restoration.

Restoration in the 21st Century (2007–present)

Ongoing conservation efforts in the 2010s have gradually returned attention to the high altar, with the benefit of new funding and research. In 2013, the Monastery Trust secured a major Heritage Lottery Fund grant to undertake the “next phase” of restoration, explicitly including vital stabilization and repair of the altar areas.

Trust officials acknowledged that the ornate altars had “been deteriorating badly” and that the initial 2007 rescue “never had enough money… to repair the altar” fully. The 2013–2015 project brought skilled craftspeople back on site to conserve stonework, original Pugin stencil paintings, and other artistic elements that were at risk. Crucially, this phase enabled professional attention to the high altar’s reredos: crumbling sections were consolidated, loose pieces reattached, and missing structural supports repaired. The Monastery’s founders stressed that without this intervention, “many of the original works of art [in the church]” – the high altar foremost among them – could have been “lost forever”.

A fortunate development for the altar’s restoration was the discovery of original design drawings by Peter Paul Pugin, which provided accurate guidance for reconstruction. Using these plans and historic photographs, the Trust has envisioned a faithful restoration of the high altar’s missing details. Conservation experts noted that although the “marble and Caen limestone reredos was… damaged,” the majority remained intact, making restoration feasible.

The carved saints and angels that had been lost from the reredos were identified in archives, and some sculptural elements (like the 12 large limestone statues of Franciscan saints that once lined the nave) were actually recovered and returned. (Those statues had been removed and sold in the 1990s, but were found listed as “garden ornaments” in an auction; they were rescued, stored, and after 16 years finally restored to their plinths in 2012.) This momentum highlighted the high altar’s significance and galvanized fundraising for its full restoration. According to the Monastery Trust, about £400,000 would be required “to return the French limestone altar to its former glory.”

As of the mid-2010s, substantial work has been done: the high altar’s structure is stabilised and cleaned, with its surviving Gothic details preserved, and protective measures in place to prevent further decay. By 2016, the monastery’s major capital works (including a new visitor wing) were completed, marking the end of its 20-year rescue journey.

Today, the high altar of Gorton Monastery stands once more as a striking historic centrepiece in the Great Nave. While it still bears some gentle marks of its turbulent history, the altar’s soaring canopies, clustered shafts, and delicate carvings have been safeguarded for future generations. Ongoing plans aim to fully restore the missing carvings and polychrome finishes when funds allow, using Pugin’s original design as a blueprint.

Even in its partially-restored state, the lofty reredos continues to inspire visitors with its Gothic grandeur – catching daylight from the clerestory and serving as a tangible symbol of the building’s resurrection from dereliction. In sum, the high altar of St Francis, Gorton, with its rich architectural detail and dramatic restoration story, remains a focal point of both the church’s 19th-century artistry and its 21st-century conservation efforts.

Appendix: Additional Context and Commentary

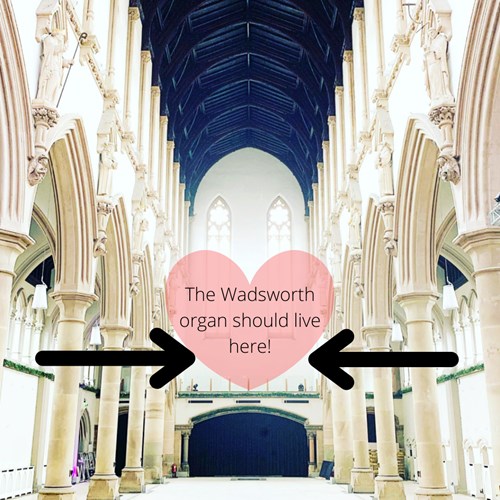

Beyond its architectural record, the Gorton Monastery high altar has been the subject of much admiration from visitors and media, underscoring its aesthetic and cultural significance. The Monastery’s breathtaking design has earned it comparisons to the world’s great monuments – for instance, “Manchester’s answer to the Taj Mahal,” as the Monastery Trust’s chairman quipped when describing the spectacular interior. The combination of lofty space and intricate altar backdrop creates a stunning venue. Modern tour guides highlight “the dramatic interior” of Gorton, noting in particular how its “cathedral high altar” and stained glass provide a picture-perfect backdrop for events and photography.

Visitors frequently remark on the atmosphere and visual impact of the high altar. One TripAdvisor reviewer, for example, praised “the nave and high altar [as] beautifully lit,” referring to the way sunlight and illumination highlight the altar’s features. Wedding parties and photographers also sing the Monastery’s praises; the Gothic arches and “intricately decorated altar” are often cited as unforgettable elements of the venue’s charm, framing wedding ceremonies with a regal, almost fairy-tale grandeur.

Such commentary attests that the high altar – even after years of hardship – has retained its ability to inspire awe. Where once it was the devotional heart of a thriving church, it now also serves as a cultural and artistic icon. The reverence it commands is summed up by the successful restoration itself: a local community’s determination to save a beautiful piece of Manchester’s local history, so that the ornate high altar and its sacred art continue to elevate and enchant all who experience Gorton Monastery’s space.